as the day breaks and shadows flee away

Anzac Cove | Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey

It's been 17 years since I first learned In Flanders Fields by heart. A chorus of 13 year old girls dutifully reciting; children who had never known war or conflict, who were far more concerned with gossiping about boys than the stories of a war long past.

But here I am so many years later, on a different continent, at the place it all happened.

And unexpectedly, I am in tears.

It starts with Atatürk's message.

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives …

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets, to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours …

You, the mothers, who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears.

Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace.

After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.”

I went to Gallipoli prepared for it to be sobering and sad; I knew that there would be stories of horror, death and disease. But I wasn't prepared for a speech of compassion, condolence and humanity from the 'enemy'. Maybe because my knowledge of the war was so patchy, I'd never considered the Turkish side. I didn't really know how Turkey fitted into the Great War. I didn't even know who Atatürk was.

After that, it's the graves that get you. We've heard the stories. That the war was romantic, that young boys put up their ages to go to fight, that it was a great adventure.

But as you walk through the graves, and read the messages chosen by the families, you can't help but feel how futile the whole thing was. Nine months of conflict, over a hundred thousand dead, and no gain made. No win. A silent withdrawal.

Next year will be 100 years since the Gallipoli horrors. The guide keeps speaking of the 'Gallipoli Campaign', as though they tried to disguise sections of the war behind softer words. But as we visit the different sites, as we walk through the remains of the trenches, the stories become real. The landscape today is green and fertile, but 100 years ago there were no trees and there was no shelter. We visit the beach where they landed by accident, and see the sheer incline of the hill in front of them, that they ran up in less than an hour.

But throughout the trip to Gallipoli, we hear time and time again of stories of shared camaraderie across the enemy lines. From the Turkish soldier who broke the battle lines to carry an injured Australian soldier to safety, to stories of how in times of cease-fire, they would chuck presents to each other from the trenches - sweets and dates from the Turks, packets of tobacco and tins of bully beef from the Allies.

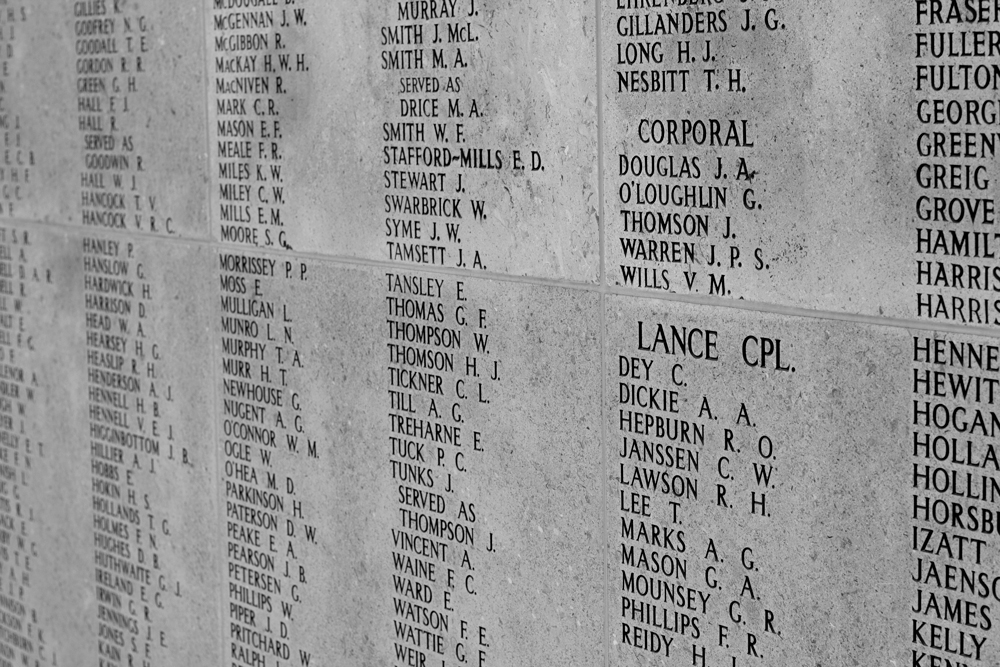

What is also heart-warming is the scores of Turkish people at the Turkish memorials. Tour bus after tour bus of people coming to pay their respects to their soldiers lost at the Campaign. On both sides, our boys fought and died because our countries told them that they must. The etched names of the fallen, stretching on and on. But even these names hide stories. Our guide shows us James Martin's name - the youngest soldier who died at Gallipoli, aged only 14.

When we leave, our group lapses into silence. As children of peace, we can never fully understand what happened there, but I'm glad to have visited. If I'm honest, I had thought more New Zealanders had died. 2,700 is not a small number by any means, but I think the way that this war has entrenched itself in our collective conscious as a nation is important. We haven't had great battles as a country, we don't have the long and complicated history like other more ancient civilisations. Our young men signed up for a war on the other side of the world, in a country that few had scarce dreamed of. They signed up for adventure and excitement, knowing that they might not return. And many didn't.

You can't help but draw comparisons to today, and wonder if our more selfish and indulgent generation would ever be able to do what those young people did before us. I'd like to hope that we could be so brave.

“In Flanders fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.”